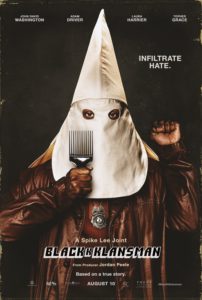

When I started working on Speak Truth to Fire over ten years ago, I had no idea that the Ku Klux Klan and white nationalists would experience such a powerful resurgence. I had no idea that the Klan’s rise to power nationwide in the 1920s would be repeated today. Nor could I have guessed that I would be publishing my novel so soon after a Spike Lee movie also focused on the KKK in Colorado.

Spike Lee’s BlackKlansman is incredibly powerful, but also fun, an amazing balance that Lee is an expert at creating. It’s based on the true story of Ron Stallworth, the first African-American cop in Colorado Springs, who infiltrates the local KKK with the help of a white officer. Lee puts forward important questions of race and social activism. He represents multiple viewpoints on these difficult questions and gives us no easy answers. The film also has some insightful and powerful things to say about the difficult issue of passing. But there are a couple of facts about the KKK that the film misses. One I can see getting cut just out of time, but the other is part of a fundamental blindness in the narrative that’s worth calling out, in part because it’s my blindness, too.

When Black Power and White Power Clash

There’s a moment in BlackkKlansman where we cut back and forth between two groups chanting. Klansmen chanting “White power!” are juxtaposed tightly against a student group shouting “Black power!” In this moment, Lee has carefully constructed the two different gatherings so that it’s easy to see where his sympathies lie. (Hint: It’s not white power.) But this is a rare moment of clarity. Usually, the movie focuses on the tough choices people have to make. Good and evil may be straightforward, but what to do about it is not.

There’s a moment in BlackkKlansman where we cut back and forth between two groups chanting. Klansmen chanting “White power!” are juxtaposed tightly against a student group shouting “Black power!” In this moment, Lee has carefully constructed the two different gatherings so that it’s easy to see where his sympathies lie. (Hint: It’s not white power.) But this is a rare moment of clarity. Usually, the movie focuses on the tough choices people have to make. Good and evil may be straightforward, but what to do about it is not.

One of the biggest issues the movie confronts is whether you can change the system from the inside. This is Stallworth’s belief. His girlfriend, Patrice Dumas, president of the Colorado College Black Student Union, disagrees. She is a firm believer that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. The police are too complicit in the white power structure to ever be steered in favor of black liberation. Instead, violent revolution may be the only path to liberation. The movie gives adequate support in favor of both viewpoints.

Some argue that this is a false balance, that Lee has skewed the story in favor of trying to make the cops seem more sympathetic and fair, but also eliding important facts about the truth of the case. For example, Boots Riley pointed out that Stallworth actually spent three years infiltrating African-American radical organizations in addition to investigating the Klan. This is important to point out, but it’s not as if this fact is completely taken out of the movie. It’s condensed for time, and Stallworth’s character is forced to confront that this action could be construed as treason against his community.

Metatextual Power

An important aspect of BlackkKlansman is that it consciously points out that it’s a fictitious representation of true facts. First, it starts with the declaration that the movie is based on some “fo real, fo real sh*t” [censor in original]. Then it cuts to Alec Baldwin as the Klan mouthpiece Dr. Kennebrew Beauregard. Baldwin, who has uproariously lampooned Trump, shows the constructed nature of white hate, the puppeteering that gets whites overloaded with unearned indignation to give their lives (and, more importantly, their money) to the Klan. In the middle of the film, Stallworth and Dumas frame their discussion of how to change the system in reference to numerous films where black protagonists take a stand against The Man, such as Shaft and Coffy. Stallworth seems to find hope in these representations, but Dumas says they are powerless to really change anything.

In the end, it’s Dumas’ viewpoint that wins out here. The important work of social change is left to us.

The Perils of Passing

Passing is a very important theme in BlackkKlansman. The theme is only briefly discussed explicitly, when Stallworth’s “white” partner comes to terms with the fact that he’s a Jew who’s been passing all his life. Because his skin is fair and he’s not devout, he can pretend to be a white man and not suffer the consequences of Antisemitism. Stallworth admits that there are black people who also pass because their skin is fair. There’s definite disdain in his voice, and he is highly critical of Zimmerman.

The criticism is justified, but Stallworth has to come to terms with the fact that passing is his profession. He’s a police officer who can pass for a black radical. And he’s a black man who can pass for white on the phone. And in that way, the ability to pass is an essential power to destabilize the ideology of the Klan. If the only way to tell a black man from a white man is to look at his face, it casts serious doubt on the notion that one is a superior race.

Passing is something I struggle with in terms of my personal racial identity. There is no doubt that most of the time, I benefit from the ability to pass as white thanks to the color of my skin and hair. Now that I keep my hair relatively short, shaved off my sketchy goatee, and stopped wearing a trench coat around all the time, I don’t get stopped by police on the street or in my car. When I do go to court, judges and AGs are lenient on me. I don’t enter a job interview with a burden to overcome racial stereotypes.

But, as it always does, passing comes with a downside: you have to give up ties to your ethnic community. In elementary school, I was the only “white” kid who walked home in our predominantly Chicano neighborhood, and that made me a natural target for bullies. Thank goodness for forced integration. Otherwise, my elementary school years would have been lonely and tormented indeed. With white kids being bussed in to my local school, I had a community where I was welcomed. Not to mention academic programs that might otherwise not have been available at my inner-city school.

Passing also sets you up for some uncomfortable confidences. After we moved to a more suburban neighborhood, I walked home with a Vietnamese friend. One day as we’re walking past a shopping center that was dominated by Vietnamese restaurants, grocers, and retailers, we notice one storefront with Spanish writing. My friend suddenly complains about all the “Beaners” moving into the neighborhood, and I realize “That’s me he’s talking about, only he doesn’t know it.” And I have to listen to his tirade. It’s like one of those scenes in movies where a person outside an open door hears all the things people say about them behind their back, only in this case, they’re saying it right to your face, with all the same unabashed malice. As a kid, I didn’t know how to deal with this, and, maybe I still don’t.

I recently learned something that reminded me just how complex and old a phenomenon passing is. My sister recently got a genetic test, and most of it was as expected: German, Iberian, Native American. The surprise: Irish. We’d always been told that we were English, which means that somewhere in our past, one of our ancestors decided they didn’t like anti-Irish racism and decided to pass as English. The notion that someone Irish would want to pass as English drives a wedge into the modern hegemonic construction of whiteness in America.

Because of my own experience with passing and the importance of passing to racial anxieties in the 1920s, I knew that I had to have passing characters in Speak Truth to Fire. One of these characters is obvious, others are more subtle.

What the Movie Missed about the Klan

Overall, the movie does a good job of showing the way the KKK works, its membership, operations, and motivations. But there are a couple things I would have liked to see better represented in the movie.

First, the movie does a disservice to the Klanswomen. On the one hand, we might hope that women wouldn’t be involved, but the truth is that Klanswomen were a major force in the Klan’s operations. They were organizers and recruiters. They helped hold the Klan together, and they were usually present at meetings, although sometimes they would run something of a parallel meeting to the men’s. Women wore the robes, too, although often they didn’t cover their faces.

This omission is mostly important because it helps expose an important limitation of the story: it’s still very much a man’s story. Men control the action, and the women take limited parts. They’re lucky if they get to speak, or if a man deigns to give them a role in his grand design. This is a little disappointing, and I’d like to think that Lee could do better. To be fair, it is hard for men to tell women’s stories. In the end, the best way to ensure women’s stories are being told is to make sure that women storytellers have access to the platforms they need to express themselves.

The other thing the movie didn’t represent well is the fact that the Klan was also partly a scam, a Ponzi scheme. Organizers played on the racist sentiments and fears of their audience to try to bilk them of money. There were the dues and the robes, of course, but there were always more things to buy. The Klan offered premium memberships in the form of a special degree that enabled them to join a higher order. In fact, there were four orders of membership, each with a higher price than the one below it. There were special pins and rings and other jewelry for people to buy. And, of course, the people at the top of the organization raked in the money. It’s estimated that Colorado’s Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke, earned about $50,000 a year from Klan dues alone, an income that would put him in the top 0.2% of earners in the US in 1923. To paraphrase H.L. Mencken, “Nobody ever went broke overestimating the racism of the American public.”

This omission is not as serious. There’s a brief allusion to it, and, of course, the movie only has so much time to deal with the ideas. So, in my opinion, this omission is understandable. But it’s important to remember that Klan members are chumps who have been brought into the organization primarily to be bilked of their hard-earned money. The racism and pageantry is just a fairly high form of the pickpocket’s distraction. “Vultures. Vultures everywhere.”

Overall, BlackkKlansman is a well put-together movie that’s passionate, nicely paced, and fun. And along the way it manages to deal with some serious issues. Plus it leaves you with a real punch in the gut. Highly recommended.