I’ve been a Godzilla fan for as long as I can remember. Like most kids my age, I spent many a Saturday in front of the TV, watching all the monster movie reruns channel 2 threw at me. I remember having at least one discussion with my mom about why I didn’t like the kind of monsters she liked. I liked giant monsters. Especially Godzilla.

Most people grew out of their fascination with these giant beasts. I grew into mine. When I learned that the origin of monster is “monstrum,” an omen, I realized that monsters always had something to tell us. Especially Godzilla.

Because I’ve spent time exploring the inherent meaningfulness of Godzilla, I’m a bigger fan than I ever was. It’s something I’ve shared with my wife and children, who are all passably literate in the lore of Godzilla. So when we visited Godzilla’s homeland in June, I knew it would be great. But I was not prepared for what really happened.

The kids adopted Shin Godzilla as the Godzilla mascot for the trip, and came home with a yearning to see the Shin Godzilla movie. And when they saw it, they loved it, despite the fact that it’s probably the talkiest Godzilla movie ever. But it shouldn’t have been surprising. While touring Godzilla sites in Japan, I learned that Shin Godzilla is the movie truest to the monster’s soul.

Godzilla, the Cosmic Constant

The most striking thing about Shin Godzilla is that it mutates. Over the years, many of Godzilla’s foes have been mutable, starting with Mothra, but also including Hedorah (The Smog Monster), Biollante, Destroyah, Orga, and even the incarnations of Gigan and Ghidorah in Godzilla: Final Wars. However, there is usually an attempt to make Godzilla immutable. From his origin as an ancient monster (and identified with an island god) in Gojira through each of the reboots, there has been an attempt to show that Godzilla is eternal and unchanging.

One way Toho does this is by making each reboot refer back to the original movie as if none of the intervening movies happened, eliding the numerous changes the monster has been through over the decades. Toho does this in 1984, 1999, 2001, and 2002. Yes, there are practically three consecutive Godzilla movies in which each one denies the existence of the others and represents itself as the one true version of the monster who hasn’t been seen since its initial appearance and destruction in 1954.

The Heisei series (1984-1995) even goes so far as to assert that Godzilla isn’t just immutable and indestructible, it’s inevitable. When Americans from the future conspire to travel back in time and substitute their own monster at the moment of Godzilla’s creation, Godzilla gets created anyway in a completely unrelated event thousands of miles away. Godzilla may not always have been, but it always must be, and humans have no power against this force of destiny.

The closest the series comes to allowing Godzilla to change actually asserts his immutability. Also in the Heisei series, a baby Godzilla is discovered and matures over the course of several movies. Much better than the original Minilla, this creature builds sympathy as it grows. It is initially very different from the adult Godzilla. But as it matures, it comes to look more like its parent. (Predecessor? There’s not a lot of talk about the genetic link between the two.) Most importantly, the baby is able to take up the mantle of Godzilla when the old one melts down in spectacular fashion. The King of the Monsters is dead. Long live the King!

A Mutable Monster

Significantly, Shin Godzilla is the first reboot that doesn’t presuppose a 1954 appearance by the monster. This frees them up to have the monster mutate throughout the film. The initial monster looks almost nothing like its antecedents. As it shuffles onto land, it looks like some strange amphibian Muppet monster. Yeah, there’s more than a little Kermit in those eyes. And boy, does it look cute. At least, until it starts spouting hectare-feet of blood from its quivering gills.

Then it stands up and begins looking a bit more like itself, but it’s not done changing. It transforms into a partly crystalline entity. Its mouth splits open in a fashion that vaguely resembles the Demogorgon of Stranger Things, although it more closely mirrors the mutant fish of Korea’s most successful monster movie The Host. And the ending of the movie hints at an even more terrible mutation. (Frightening or idiotic? I’ll let you decide, because I’m on the fence.)

This change in the movie acknowledges what none of the other movies admitted: to survive, Godzilla has had to change. Godzilla is not a Grecian urn. It is an omen that speaks different messages to different ages. When it needed to be a protector of children, it could do that. It wrestled ridiculous foes, set upon us by even more ridiculous masters, including tubby British-looking Atlanteans and an absurd array of aliens, including space cockroaches, space apes, and even, yes, space rocks. Later, Godzilla represented or fought foes who represented the ongoing specter of nuclear power, GMOs, trade disputes, and even the cultural appropriation of its own identity. In possibly its most impactful appearance, Godzilla represented the war guilt of Japan, becoming infused with the angry souls of those killed by Japanese atrocities in WWII.

This change goes hand-in-hand with Toho’s acceptance of the new American Godzilla, and their willingness to make Godzilla movies in parallel with the ongoing “Monsterverse.”

Modern Tragedy

So it’s not a surprise that the new Godzilla represents a new, different tragedy. The original Gojira reflects a society that was beset by fire. You can see the anguish of a people who saw their cities, their culture, and their children burned. This is the terror of the original monster. It is the firebombings of Tokyo as well as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki accreted into one horrific essence.

More than perhaps any other monster movie, Gojira lingers in the makeshift clinics where the wounded cry with suffering and shock. People struggle to understand what they went through. The movie gives its Japanese audience a fantasy of relief. Their country developed its own superweapon, more powerful and devastating than the atomic bomb. Its creator nobly sacrifices himself to save the world from a new arms race. But in Gojira, the suffering is so real that it pokes through the veneer of fantasy.

Shin Godzilla represents a different tragedy. It is written to reflect the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. When Godzilla emerges onto land, it pushes a wave of water before it, washing small boats and cars away before it.

This Godzilla also represents a different kind of radiation. Instead of burning fire, this is the kind of radioactivity that contaminates, seeping into everything and poisoning the city. Frequent references to specific radiation levels in sieverts shows that the audience is intimately familiar with radiation exposure, due to the Fukushima Daiichi meltdowns and releases of radiation.

Political Satire

Shin Godzilla is also a very funny movie in parts. The humor comes from its satire of the political response to Godzilla. William Tsutsui is right to note that there is a serious message here: “Shin Godzilla leaves no doubt that the greatest threat to Japan comes not from without but from within, from a geriatric, fossilized government bureaucracy unable to act decisively or to stand up resolutely to foreign pressure.”

The movie also grapples with Japan’s discomfort over ongoing military restrictions. The movie takes a lot of time agonizing over when and how Japan is authorized to use its military force. It represents the country as hamstrung by these restrictions, even in the face of an imminent threat like Godzilla. The movie goes so far as to flash Article 76 of the Japan-US Security Treaty on the screen as the government struggles to determine its response. It’s in Japanese, but the government officials mull over its meaning. They are stymied by the fact that the use of Self-Defense Forces is only allowed in response to “armed attack” by an outside nation. While this is happening, we see bodies crushed under cars, and families killed in their living rooms as they struggle to ready their child for evacuation. The pain is real.

But on the other hand, the movie is deliberately funny about the government’s paralysis. The first few decisions ministers make just move them from one conference room to another. After taking an emergency briefing the Prime Minister complains that his noodles are soggy. Then he says, “I knew this job wouldn’t be easy.” Such a sacrifice for the people. Amid the round-the-clock work schedule, the movie makes jokes about stinky shirts. It was hard to appreciate the humor when I first saw it. Having seen it a few times now, I think it’s the Godzilla movie with the best intentional humor.

Somewhere between the tragedy and the comedy, the movie struggles with the internal conflict of politicians. Do they want to be the ones who do what must be done? Or do they want to be the ones that stay in politics and move up the ladder? These goals should be complementary, but the movie poses that, all too often, they’re not.

Learning to Live with Godzilla

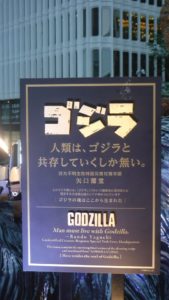

Given that one of the movie’s themes is the eternal nature of Godzilla, it’s not surprising that the monster doesn’t die. Instead, we are told that “Man must live with Godzilla.” In the movie, of course, that’s intended to be an ominous statement, as the monster still looms overhead, threatening, albeit disabled (temporarily). But to Godzilla fans, nothing could be better. It’s a promise that the future will hold more Godzilla. And so far, that promise is holding up.

Since Shin Godzilla, we have already had two Godzilla anime movies. I’m not sure how I feel about them, except to say they’re better than the animated Godzilla shows in the 70s and 00s. But they are definitely Godzilla. Plus, there’s a third movie in the series coming out later this year. And then there is Godzilla: King of the Monsters, which released in 2019. Here’s the trailer:

Plus, we have a new Godzilla vs. King Kong to look forward to. And a sequel to Shin Godzilla, possibly as soon as 2020. It’s a great time to be a Godzilla fan.